Kush, Maryjane, Reefer, Pot, and Grass are a few of the many names for the controversial drug cannabis. For some, cannabis is a Godsend, a natural plant helping people relax and treat pain, depression and anxiety. But for others, it is a dangerous ‘gateway’ drug, stereotyping cannabis users as lazy and unreliable. There’s a social stigma that cannabis consumers face; despite the general attitudes towards the plant changing, people still treat drinking and getting stoned very differently.

Beyond recreational smoking, cannabis is a multidimensional plant that can be used in different aspects of life. Therefore, our perception and feelings about the plant should not be rooted in fear and biased information (demonising the drug or trivialising it and claiming it’s not addictive and is completely harmless). I am tired of cannabis stigma and the refusal of society to accept that their rejection of the plant in its entirety is a continuation of the racist propaganda aimed at arresting and policing black people. So, as it’s 420, I’ve decided to write about the racist history of cannabis laws in the US.

Cannabis did not always have a bad reputation. It originally evolved in Central Asia and was introduced into Africa, Europe and the Americas. The first recorded use of cannabis was by Emperor Shen-nung in 2000 BC. Historically, cannabis was used for ritual and medicinal purposes through either oral ingestion or smoking. For example, the drug was introduced into India between 2000 B.C and 1000 BC. It was widely used and celebrated in one of the ancient Sanskrit Vedic poems as one of the ‘five kingdoms of herbs… which release us from anxiety.’ However, cannabis is no longer synonymous with medicine, relaxation or healing. Instead, it is now a heavily policed drug across the world.

US History

Cannabis arrived in the US from the south during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After the Mexican Revolution of 1910, Mexican immigrants moved into the United States, bringing the recreational use of cannabis. The plant became associated with minorities, and perceptions of the plant were linked to white prejudice against minorities. The plant’s name, cannabis, was changed to ‘marijuana’ to connect it to its ‘Mexicaness’. Anti-drug campaigners warned against the encroaching “Marijuana Menace” and cannabis was essentially criminalised through the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937. The law was based on research headed by Harry Anslinger, who was at the centre of a brutal and racially motivated anti-cannabis campaign.

Anslinger who was the first director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics did not hide his racism. He said:

‘There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the US, and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers, and others.’

He also found several cases where people had committed violent offences and claimed that cannabis was the cause. A significant case was Victor Licata, a young Italian man who had hacked his family to death. Anslinger consulted 30 doctors to confirm his claim that the violent crime was linked to weed. Of those, 29 said there was no connection, so he pushed the conclusion of the one dissenting doctor to the public.

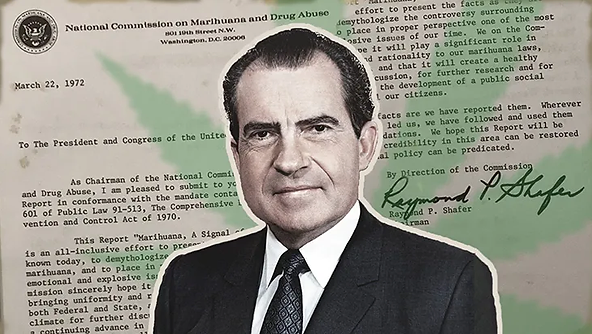

Continuing Anslinger’s work, the Nixon administration introduced the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), which classed cannabis as a Schedule 1 drug. This was a purely racist law. Despite the Shafer commission concluding that cannabis is not harmful and that small amounts should be legalised, the opposite was done through the CSA. Nixon was less interested in understanding cannabis and more so in policing minorities through his ‘war on drugs.’ His senior advisor John Ehrlichman said:

‘We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalising both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.”

Ehrlichman was successful in his plan, as millions of African American men have since been incarcerated over cannabis charges. Unfortunately, with Raegan cementing the legacy of the war on drugs, African American men continue to be the biggest victim of the racially charged campaign against cannabis.

A culture shift?

You may think that cannabis is now normalised due to the growing legislation decriminalising the plant globally and popular culture shedding a more positive light on it. However, black people are still disproportionately targeted and jailed over cannabis offences, and cannabis is still stigmatised and labelled as a ‘gateway drug’ despite no science supporting this. Of the 8.2 million cannabis arrests in the US between 2001 and 2010, 88% were for simply having cannabis. Nationwide, the arrest data indicated one consistent trend: significant racial bias. Despite approximately equal usage rates, Black people are 3.73 times more likely than whites to be arrested for cannabis.

The cannabis charges are also incredibly disproportional to the crime. For example, Cooper Corvain T. Cooper was sentenced to life without parole for participating in a conspiracy to distribute marijuana from California to North Carolina. In a country where cannabis is partly legalised, he was given a life sentence for a non-violent crime under the federal ‘three strikes law’ because he had two previous charges for marijuana and codeine. Black people like Corvain are more likely to be prosecuted for drug possession than white people. Coupled with laws like the three-strike laws, the stigmatisation and criminalisation of cannabis continue.

Black people are more likely to be arrested over cannabis. This also means that the communities punished the most over the criminalisation of cannabis are benefiting the least from its legalisation. One would think that since cannabis was only made illegal as a way to detain minorities, they would be prioritised in the legalisation of the industry. In the United States, sales of legal recreational cannabis are expected to reach an estimated 25 billion U.S. dollars by 2025. However, in 2017, 81% of marijuana business owners in the U.S. were white, 5.7% were Hispanic, 4.3% were Black, and 2.4% were Asian. Black people face many pedestals for benefiting from marijuana legalisation; for one, the decriminalisation of cannabis has not slowed down disproportional arrests. Two years after decriminalisation in Washington DC, a black person was still 11 times more likely than a white person to be arrested for public use of marijuana, even though Black residents use cannabis at similar rates to white residents.

What about the rest of the world?

The over-policing and harsh criminalisation of cannabis are not unique to the US. Cannabis was criminalised in the UK in 1928 under the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1920. The Misuse of Drugs Act currently lists cannabis as Class B controlled drug. Interestingly, the UK was once one of the world’s largest exporters of cannabis for medical use and produced around 95,000 kilograms of cannabis in 2016. It is somewhat ironic that a country willing to export cannabis in such high quantities for medicinal and scientific purposes has prohibited its use within its borders.

Under stop and search, police officers can search you if they have ‘reasonable grounds’ to suspect you are carrying illegal drugs. The Ministry of Justice reports that black people made up 16% of drug-related stops and searches in 2020 despite only making up 3% of the population. The racial bias is evident, especially as there are no statistics that show that drug use is more prevalent amongst black people. Instead, statistics have shown the opposite; 2018/2019 findings of adults aged 16 to 59, 8% of the white respondents versus 6.7% of the ‘Black or Black British’ respondents reported use of cannabis in the previous year.

The attitudes and effects of criminalising cannabis and spreading misinformation about the plant did not only occur within the borders of the US and UK. Japan is known for having some of the harshest laws against marijuana. However, it wasn’t Japan that criminalised cannabis. Instead, the occupying US government prohibited the plant in 1948 while Gen. MacArthur was the head of the U.S. Occupation Forces in Japan; he introduced the Cannabis Control Act. Harm is not the issue with how cannabis is treated in Japan. Instead, it is about legality, and because usage is increasing, the government wants stronger laws, so they need to reinforce the idea that cannabis is harmful. Japan previously had a very healthy relationship with the plant. Although it wasn’t smoked, it was integral to their industry and commerce. Yet, most Japanese know little about the true nature of cannabis. Director of the Japanese hemp museum, Takayasu, said, “the image surrounding hemp grown in Japan was ruined, due to American hippies and soldiers returning from Vietnam smoking marijuana” in the 1960s. In other words, US propaganda on cannabis affected how the Japanese viewed the plant.

Concluding thoughts

The reasons for criminalising cannabis have nothing to do with the plant itself and whether it is harmful. Instead, certain governments have been using cannabis criminalisation to target the black community.

Science has repeatedly shown that cannabis is no more dangerous than alcohol or tobacco. Nevertheless, the historically racist misinformation spread about the plant continues. Perhaps the criminalisation of cannabis has not been effective because it simply doesn’t make any sense. It prevents the possibility of people learning about the dynamic nature of the plant and being able to use cannabis safely and responsibly in various ways. Instead, it sends mostly black people into the criminal system and exacerbates the misinformation and stigma around the drug its users. Continuing the propaganda that cannabis is just a dangerous gateway drug is irresponsible and promotes an equally extreme counter-narrative that may trivialise the plant with people claiming that it can never be harmful and cannot be addictive. We need to dispel the political and racialised view of the plant to allow for a holistic understanding of it.

Other Sources

Alex, McCandless., 2017. ‘Cannabis Activism in Japan, Yes That’s a Thing’, High Times HOW WE RISE

Browne, R., ‘Canada’s legal weed industry has a diversity problem’ Vice

Cooper, WL. and Thompson, C., 2019. ‘Will Drug Legalization Leave Black People Behind?’, The Marshall Project.

Hudak, J., 2020. ‘Marijuana’s racist history shows the need for comprehensive drug reform.’

Morgan, J., 2021. ‘Black Women Are Calling For The Decriminalisation Of Cannabis — Here’s Why’ Refinery 29

Morris, S. ‘‘Systemic racism’ experienced by black communities through UK’s drug laws, says former government adviser’ Sky News.

Netflix Documentary, 2019. ‘Grass is Greener’

Waxman, O.B., 2019. ‘The Surprising Link Between U.S. Marijuana Law and the History of Immigration’ Time.