“You have no idea, do you, she says. How could you? They don’t teach you any of this. Too unpatriotic, right, to tell you the horrible things our country’s done before. The camps at Manzanar, or what happens at the border. They probably teach you that most plantation owners were kind to their slaves and that Columbus discovered America, don’t they? Because telling you what really hap- pened would be espousing un-American views, and we certainly wouldn’t want that.

Bird doesn’t fully understand any of thesethings, but what he does understand, suddenly, and with head-spinning force, is how much he doesnot know.

I’m sorry, he says meekly.

The librarian sighs. How can you know, she says, if no one teaches you and no one ever talks about it, and all the books about it are gone?

A long silence unwinds between them.”

(Ng, 2020, p. 114)

PREFACE

In 1945, Korea hung the red and blue Korean flags on every building and street to celebrate our independence – to celebrate how we could speak our language again, have our food, wear our clothes, and not have to fear getting beaten up or spat on by the Japanese police on the streets. Yet, what was waiting for Korea was not sovereignty but the 38th parallel the US drew, the US military government ruling us, and the Korean War ripping our peninsula into two pieces. For most of the current Koreans, our land has been divided into North and South Korea for as long as we can remember.

Over the past seven decades, the modern identity of South Korea formed around the great other – the US. The presence of America within our country grew to be so saturated that there is a bizarreness in how South Koreans see more of the US than Korea within our country (Kim, 2005; Yim, 2009). South Koreans adapted to the eyes of the white Americans seeing the knowledge and value of the West as superior to ours, and we got used to envying and seeing the US as a model of advancement. In our country, direction towards America is a desire. What gets overlooked in the process of running towards these desires, whether as a country or as individuals, is how our country’s intimacy with and dependency on the US changes individual narratives of Koreans.

The current position of South Korea bound to the US impacting South Korean bodies and minds gets left out in most research on South Korea’s Americanization published in the West, especially in the US, and rarely gets recognized amongst South Koreans. In this study, I combine research done by scholars from South Korea and the West, together with lived experiences of current South Koreans, to study the phenomenon from both the involved and observant perspectives, inside and outside Korea.

In the first chapter, I discuss South Koreans’ familiarity with and desire for American values and knowledge. To understand how other South Koreans perceive and experience the US within our country, I did case studies on five South Koreans – my parents, who are in their 50s, and three other South Koreans in their 20s and 30s – over three months through biweekly interviews and group conversations (Appendix A). To see the image of America that a wider South Korean public is exposed to, I analyzed the American contents on the two main local online portals most used in South Korea – Naver and Daum – and looked at what values and bodies of the US were shown between 17 February and 20 March 2023.1 In the second chapter, I write about how our country’s closeness with the US impacts the lives of the current South Korean individuals, either in my family or my interviewees.

Chapter 1: How do we, South Koreans, get closer to America today?

When beginning to form this research, I sat down to think about what South Korean society is composed of and what makes our country South Korea, but I could not think of an area in our present South Korea that does not have a touch of America. H. Ryu shared how she realized “most parts of our country have been either Americanized or Westernized that it has become difficult to find what is Korean” (Personal interview, 18 February 2023). While discussing why there is America anywhere and everywhere in our country with my interviewees, I noticed how most described it as a natural phenomenon that our country experiences in advancing. How did we get so close to America and get used to our closeness with it that we find seeing more of America than Korea in our country as natural?

1.1. Familiarity

가랑비에 옷 젖는 줄 모른다.

I spent the first few weeks of my research focusing on the sentimental closeness and familiarity my interviewees and I have had with America while living in South Korea. We grew up shortening our emotional distance from America through our exposure to tangible materials such as American films, toys, food, electronics, or the systems and laws that compose the structure of our country. From the responses of my interviewees, I found how materials and values from the US have been received in our country as a model for the modern. In all our memory, American products were signs of luxury in our homes, and they were the most preferred in our markets in South Korea until the early 2000s; H. Ryu described, “anything tagged made in the USA was most popular” (Personal interview, 18 February 2023).

I noticed that all my interviewees did not perceive American influence and presence in our country negatively as a cultural replacement or erasure; we instead learned during our lives to connect the cause of our country’s Americanization with the difficult situation brought by the Korean War, and that receiving American influence and support was reasonable and necessary in modernizing our country. Beyond preference and dependency on American materials, we got used to seeing America as the other that helped us rebuild and improve our country after the Korean War.

Deok-ho Kim (2005) argues that South Korea has voluntarily duplicated America since its liberation from Japan. One of the reasons why we, South Koreans, do not refuse the saturated influence of America is because we are trapped in the modernization theory American scholars and politicians in the 1940s brought us, which argued Korea must adapt to the Western culture and influences and remove the old Korean traditions to modernize (Chung, 2005; 2007; 2012). The other reason is South Koreans’ sentimental attachment to the US, deriving from the narrative of seeing America as our supportive patron or friendly alley due to their military and economic help during and after the Korean War. Such positive framing and constant exposure to American materials, culture, and systems within our country over the past seven decades have blinded us, South Koreans, from seeing what the dependency brings us or the need to distinguish America separate from ourselves.

A lot of the content that South Korea creates today combines what is Korean and the image or trends of the white West that our country has taken. Two female interviewees in their 20s described how they still see a preference for white skin and tall and slender looks in South Korea over the past couple of decades. They talked about how South Korean contents still portray figures who studied or worked in the US as superior and more modern than others, building the elite white stereotype within South Korean media.

길 다지기

Placing a vertical hierarchy is a habit South Koreans have, and it is most visible in how we weigh and compare the value of knowledge depending on their origins. My interviewees describing the tendency of South Koreans to head towards the US naturally because it is more advanced than our country indicated how we are trained to put knowledge from America as superior to ours, similar to materials. The younger interviewees had described knowledge from America as elite and modern. My interviewees and I were all born into our society that has read America as the place where we could get “the technology that would help advance our country” since the 1950s (D. Kim, Personal interview, 14 February 2023). When we crawled, our land composed of hierarchy and individual desires awaited us. It wasn’t a direction made overnight; different generations of South Koreans walked on the same path, building the direction clearer over time. Whenever you think of deviating, you have the stomped-down soil reminding you of the direction to America. Whether it is a steaming summer afternoon in July or a winter morning with roads still frozen, rows and rows of South Koreans still line up for hours outside the US Embassy in Seoul every day to get their extensive visa interviews. America is a desire in our country; it is a power that allows South Koreans to succeed in our society.

“Going to the US to study was a trend during my university years in the 1980s. Students preferred to go to the US the most because it was the closest foreign country to us, and universities in South Korea had their sister schools mostly in the US. I think it is still like that today. … Friends left before you could ask them if they planned to go study abroad. Desks in the classroom emptied because those who used to sit there left to go study in America. Or to Europe, if people were short on budgets. It was one friend after another.” (K. Cho, Personal interview. 13 February 2023)

“Our country [in the 1980s] was seeking for the ones with knowledge that could improve Korean society. … The ones with knowledge from the West got accepted to the highest positions in companies and institutions the most, and that became a climate – where those Koreans who went to the US to study, came back, and became the elites on the top 10% of our society.” (D. Kim, Personal communication, 17 February 2023)

“My department [of social welfare] relied a lot on the books or articles from the US. You know, Korean universities like to emphasize the need to read original works in English, because those are the purest knowledge you get. … Most, if not all, materials in psychology, mental health, medical science were from American sources at my university in Seoul.” (H. Ryu, Personal communication, 18 February 2023)

Degrees from the US have been the golden key, the fast track, and now is “a requirement of success in South Korea” (H. Kim, Personal interview. 23 February 2023). As Thomast Kern (2005) states, “Nearly all top positions in politics, economics, education or science are occupied by the people who graduated from well-known South Korean universities and studied for several

“The desire towards America was very saturated in South Korea until recently. Just until 2017, the Shinse-gae department store in Gangnam 2 used to have upper floors with huge halls and seminar spaces reserved for their weekend classes, teaching know-how and tips on successfully migrating to the US. … American Dream was mixed with South Koreans’ obsession for English edu-cation. … It’s amazing how trends spread so fast in our country. Once someone starts doing something, soon you’ll see your neighbor following it too. It’s like a fire that starts small but ends up burning an entire mountain in the dry spring. And when you are in Korea, you can’t avoid trends, especially when it comes to education.”

(H. Kim, Personal interview. 24 February 2023)

years in the United States” (p. 8). Our parents’ generations saw people around them departing and returning to our country with American knowledge and gaining the power to build and lead our society. In the minds of South Korean mothers and fathers, America is linked with success.

The younger interviewees and I all went through the 2010s when heading toward the US became a direction of our country. In 2008, President Lee Myung-bak announced, “English ability is the competitive power of individuals and states,” and the MB administration stated our country’s need to stay close to the US as the basis for their foreign policies (An & Suh, 2013; Lee et al., 2010). After our government emphasized the need for South Korean individuals to gain American knowledge, our country’s institutions and enterprises had a wave of hiring employees with American degrees, and South Koreans hurried to go to the US. There formed an anxiety among South Koreans that made us think that whoever deviated from such direction and did not get American knowledge would be left out. In a community that highlights competitiveness the most, people fear being left out or falling out from the standards. My interviewees described how schools then began to weigh American English classes as equal to Korean or mathematics classes, and this phenomenon extended to their after-school academies and tutorials. The survival mode of learning English and going to the US became unstoppable amongst Koreans, and areas like Gangnam in Seoul became swarmed with academies and consultants guiding and encouraging parents to send their children to the US.

Terms such as yoohak yeolpung 유학열풍 3, and anchor baby 원정출산 4 floated in Korean journal articles both as the subject of criticism and envy when I was in middle school. Whether there were concerns or not, our society continued to work like a mold making copies of American knowledge and values. The danger in having so many people in our country leave to go to the US lies in how we become dependent on the knowledge we get from the white West and how South Koreans return from the US with the sentiments of Americans. South Korean scholars, especially journalists that studied in the US, have had “the patterns of creating an atmosphere that supports our country’s alliance with America”, and such bodies have taken elite positions in our society (Cha, 2018, p. 245).5 Our society grew to connect emotionally and to share sentiments with the US beyond being familiar. (Yim, 2009)

South Koreans’ familiarity with the US makes us forget how bizarre our intense obsession with America is. How many of us in South Korea, including myself in my teenage years, have desired America as we learned that we could gain power in South Korean society with American values? How many young students in our country are staying up late at night, studying and preparing for their possible future in America, just like I used to? How many of us, South Koreans, have lived reproducing the American culture or knowledge and disdaining ours, and where do our Korean roots go while we duplicate America? Have we considered what our direction towards America is doing to us?

Chapter 2. What is our closeness to America doing to us?

제국주의의 가장 무서운 무기는 제국주의자의 눈빛으로 자기 자신을 감시하게 하는 것.

Goo Yong Park echoing Frantz Fanon’s words says, “The scariest weapon of imperialism is making the colonized ones observe, supervise, and watch out for themselves and each other with the eyes of imperialists” (Kim Ou-Joon, 2023). What has lasted the longest as a consequence of America’s intervention in our country since the 1950s is the impact the intervention has brought into our minds. We, South Koreans, learn and interpret our past and present from the perspective American white knowledge gave us, which is stuck to the Cold War. Youn-jin Kim (2005) writes, “Not only did South Koreans get America’s systems and values but also learn to think like Americans and to act like Americans” (p. 25). Currently, one-third of our country confuses the direction and desire of the US for ours. Yet, as seen in most of my interviewees’ attitudes, we, South Koreans, are busy hushing each other and reminding ourselves to lower our voices when criticizing such acts because we do not want to be called anti-Americans.

Bae-geun Choi states, “There are three traumas that a country with an experience of getting colonized goes through after the liberation: political dependency, economic and technical dependency, and the dependency of consciousness” (2023, 19:17). As the second part of my research, I looked at how these dependencies of our nation impact the lives of individuals. What is the outcome of our country residing with the US military, living with American systems, values, and culture, and having sentimental closeness and allegiance to the US?

2.1 A Favor

빚 준 상전이요, 빚 쓴 종이다.

While the bone structure of South Korea since the 1950s has duplicated America, the sentiments of South Koreans also moved close to the US. Beneath familiarity, there has been gratitude and allegiance. Our country’s elders from the 1950s and 1960s saw America as our saviors and friendly patron. South Koreans have felt an owe for the support from the US during the Korean War – the owe that makes us thank them, the owe that acts as a shackle anchoring us to America. Jung-in Moon (2023) says, “Because we [South Koreans] like America so much, and the point of view of seeing America giving us support in the past makes us feel some kind of a historical duty in helping them” (51:20).

After about a decade into the Vietnamese War, the US asked South Korea to send their military troops to the battlefield to support the American army in exchange for their help during and after the Korean War. Our country could not say no; our dictator Park Chung-hee also found sending our troops in exchange for getting America’s support for another ten years of his dictatorship was fair. Families in South Korea soon began preparing to send their sons to another battlefield before the memory of the Korean War faded away. Owe is scary. Owe puts you in difficulty – it gives you a reason to sacrifice what you love even if you do not want to. My interviewee, whose father and uncle fought in the Vietnamese War, shared his memory:

“Both sons of my grandfather went to the Vietnamese War. My dad was in the Marine Corps when he was in his 20s, and he was lucky because he was enlisted as an administrative solider, so he did not have to fight in the front line. … People did not want to send their child, but how could you say ‘no’ when the whole country is doing it, and when it’s the one that previously helped you that’s asking you a favor? … My dad talked about it lightly when I was young – he shared how his family was able to buy a piece of land as a reward when they returned from the war. … The two of them suffered from aftereffects of defoliant for their entire lives. … The veterans had raised a lawsuit case against our country’s government on defoliant damage and won, but the court had only demanded the country to compensate for one person per family, so my uncle who suffered more than my dad got the compensation. … A part of me blamed those eras when my dad got diagnosed with oesophagal cancer a few years ago.” (H. Kim, Personal Interview, 4 May 2023)

The US extorting our country’s military continued. In 2003, the Bush administration requested South Korea to dispatch our troops to Iraq. In 2002, the US targeted North Korea as part of their ‘core of evils’ because they saw signs of North Korea forming nuclear weapons. When the US demanded our military, they had already been actively discussing striking North Korea preemptively, and President Roh Moo-hyun did not want another war to break out in the Korean peninsula. Under peace on our peninsula held hostage to the US, the Roh administration ended up dispatching about 3,600 soldiers in 2004, despite the South Korean public disagreeing.

Today, as the US plans another war with China over Taiwan and trains together with the military of the Philippines, Japan, and South Korea upon the title of the military alliance, the possibility of the US asking us for our troops again thickens. Jung-in Moon (2023) warns, “The consequence we [South Koreans] get from participating in current America’s alliance emphasizing a common enemy and threat that leads to another Cold War is going to be greater than what we imagine” (48:51). This time, it is not a history written in few letters on textbook or articles any-more. Clock ticks; our news announcing that another US submarine showed up by our sea, or sets of Chinese air force planes flew over our sky – yells at us that it is our present. It is a worry that all my South Korean male friends have, a concern my friends with male partners and siblings have, a fear my mother’s friends with sons have – for our country to summon them again. It is not a scenario that feels far for South Koreans, in a country where for the past seven decades, all our male citizens have gone through two years of obligatory military service in their youth and the yearly 10-day military training until they are 40. It is one of the physical ways our state reminds us not to forget the War we are still in with the North. My male interviewees told me those constant training makes their bodies remember how to behave on battlefields, and the loud sounds of rifles and artilleries make them rethink about the weight of the word war, and the need to stop and avoid it as much as possible. But whether they like it or not, when our state calls, they have to go.

“맨 처음 대통령 당선됐을 때 북핵 문제를 놓고 북한에 대한 무력 공격설이 마구 난무했습니다. 미국 신문에, 우리 한국 신문에. 책임 있는 사람들이 말했다, 안 했다는 것이 중요한 것이 아니고, 신문에 난무하면 그게 국민들은 불안감을 느끼게 되는 것입니다. 그래서 ‘무력공격은 안된다.’ 이렇게, 얘기했습니다. 그랬더니 ‘어, 저러면 미국하고 일 생기지.’ 우리나라의 그동안의 안보를, 주 안보와 안보 논리를 주도해 왔던 사람들이 ‘큰일 났다. 노무현이가 미국하고 관계를 탈 내겠다.’ 그랬습니다. 그러나, 그 이전에 제가 ‘어떻든 전쟁은 안된다.’ 그렇게 얘기를 했습니다.

심리적 의존 관계, 의존 상태를 벗어나야 합니다. 국민들이, ‘내 나라는 내가 지킨다’라고 하는 의지와 자신감을 가지고 있어야 국방이 되는 것이지, 미국한테 매달려가지고, 바짓가랑이에 매달려가지고, 미국 엉덩이 뒤에서 숨어가지고, ‘형님, 형님, 형님 빽만 믿겠다.’ 이게 자주 국가의 국민들의 안보 의식일 수가 있겠습니까? 이렇게 해서 되겠습니까? 인계철선이란 말 자체가 염치가 없지 않습니까? 남의 나라 군대를 가지고, 왜 우리나라 안보를 위해서 그것을 인계철선으로 써야 됩니까? 피를 흘려도 우리가 흘려야지요.

미국과 우리 사이에 경제적인 일이나 다른 일이 있어 미국이 ‘그러면 우리 군대 뺍니다.’ 라고 나올 때 이 나라의 대통령이 당당하게 ‘그러지 마십시오.’ 라든지, ‘예 빼십시오.’ 라든지 할 수 있어야 말이 될 것 아니겠습니까, 미국이 ‘나 나가요.’ 하면 다 까무러치는데, 대통령 혼자서 어떻게 미국하고 대등한 관계를 맺을 수 있겠습니까?

우리가 작전 통제 하나 할 만한 실력이 없냐, 대한민국 군대들 지금까지 뭐 했나, 이 말이에요. 나도 군대 갔다 왔고, 예비군 훈련까지 다 받았는데, 심심하면 사람한테 세금 내라 하고, 불러다가 뺑뺑이 돌리고 훈련시키고 했는데, 그 위의 사람들은 뭐 해서 작전 통제권, 자기들 나라, 자기 군대 작전 통제도 하나 제대로 할 수 없는 군대를 만들어 놓고, ‘나 국방부장관이요, 나 참모총장이요’, 그렇게 별들 달고, 거들먹거리고 말았다는 얘깁니까? 그래서 작전권 회수하면 안 된다고, 줄줄이 모여가지고 성명 내고. 자기들이 직무유기 아닙니까?”

2006.12.21. 민주평화통일자문회의 제50차 상임위원회 노무현 대통령 연설 중 (행정안전부 대통령 기록관)

“When I first got elected as president [of South Korea], there was a rampant rumour about attacking North Korea due to their nuclear weapon production. It was in the American newspapers and in our Korean newspapers. It’s not about whether people with power and authority said it or not. It’s about the anxiety citizens feel when such things go on a rampage in newspapers. So I said, ‘Armed attacks cannot happen.’ Then people in our country that have been leading our national security started saying, ‘Uh, that is going to lead to a conflict with the US. Roh will make a problem in our country’s relationships with the US.’ But despite all that, I earlier had said, ‘No matter what happens, we cannot let another war happen.’

We must leave our psychologically dependent condition. Our national security is an idea of our country’s people protecting our land; how can you say that begging the US, holding onto their trousers, hiding behind them, and saying, ‘Brother, brother, I only believe in your support’ is the security theory of an independent country?

If something happens between our country and the US that the US says, ‘We are withdrawing our troops [from South Korea],’ our country’s president should be able to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ confidently. But how can our country’s president have a relationship on equal terms with the president of the US when our entire Ministry of Defense freaks out and trembles in fear at the US saying, ‘I’m leaving’?

I don’t think our country lacks any skills or knowledge in controlling our country’s military. Our country has already had decades of training and experience. Our men out there spend their youth on military training, but the ones with authority say that ‘we are not competent enough to direct our own military’? So, with those stars on their shoulders titling them Chief and Minister of Defense of South Korea, what they do is make a pronouncement insisting South Korea must not collect back its operational control authority from the US?”

Excerpt from President Roh Moo-hyun’s speech from Peace and Unification Conference from 21 December 2006 (Source: Presidential Archives of South Korea)

2.2 The Red Scare

A consciousness that every South Korean wears is the red scare. The need to stay away from any signs of the reds빨갱이 has been strongly embedded in South Korean society since the 1950s when McCarthyism swept the US. It is “the common enemy” of our state, “one box in which to collect all the anger; one straw man to wear the hats of everything they feared” (Ng, 2020, p. 186). When our state does something wrong, it still blames the reds, because it works. The thought of keeping ourselves safe from North Korea and staying in alliance with America is so strong that it wipes off all other values and narratives in South Korea until today. My mother described her experience during her childhood in the 1970s and 1980s as the following:

“We used to draw anti-communism posters every year on the 25th of June at school. Now that I think about it, there were many things in my childhood that reminded us of the anti-communism mind. The cartoons or TV programs I watched while growing up all depicted communists and North Korean leaders as the devils and wild boars. … It is raising consciousness – the consciousness of refusing communism and North Korea. … It had only been a few decades since our country experienced the Korean War. Korean people still have a sharp memory of what it was like during the war and the years after. The fear and trauma of war was greater than anything then.” (Personal interview. 14 March 2023)

When discussing South Korea’s present with the US, many interviewees pointed out the bizarre scenery of our country’s conservatives protesting on the streets while holding the Korean flag in one hand and the American flag in the other. South Korean conservatives stand with a pro-US position, as they were built by the forces from the West – the UN and the US (Chung, 2012). Along with our conserva tives’ allegiance to the US, they believe the US-South Korea alliance will give our country safety and protection.

Beyond imposing the need to bring South Korea closer to the US and its ideology, our country’s conservatives believe that having the alliance means our country shares everything we have with America. They continuously argue that the US and South Korea are one community, and if South Korea shares everything we have, the US will also share theirs with us and protect us from the North and communism (Chung, 2012). Our president Yoon Seokyeol and his conservative party silenced all disagreements and questions over the last few months by arguing that any South Korean that criticizes America’s work on our country is “a power that challenges our alliance with the US” and “threats free democracy and free market ideology,” “a hostile anti-state power that supports communist ideas” and is “a Pro-North Korean force” (Choi, 2023; Kim, 2022).6

Junhee Jung says, “Our current South Korean government speaking for and protecting the US is similar to sadomasochism, or to Stockholm syndrome as commonly described, where a person that experiences constant violence from their partner does not recognize such condition as toxic and rather sees the need to stay devoted to their partner” (HASHTV, 2023, 31:49). How our current government demands our public not to question or to think of leaving America’s boundary is violent. Many interviewees expressed frustration about having no room in South Korean society to question and debate what this alliance brings to our people. I saw reluctance and hesitation from almost all interviewees when discussing our country’s relationship with the US, and most mentioned that they were being careful not to be identified as communists 공산당 or the reds 빨갱이. In a country where criticizing America for exploiting our country gets categorized as an anti-US act or a danger to our nation, it is a challenge to properly debate or reflect on our relationship with the US. My interviewees described how South Koreans never study the need to look at our closeness with and dependency on America. The lack of recognition hinders us from cutting off our dependency on America or imagining an independent future for our country.

2.3 The Erasure of Unification

눈에서 멀어지면 마음에서도 멀어진다.

As most interviewees mentioned, the biggest impact and consequence South Koreans face through our closeness with America lies in how we view our present and future with North Korea. Through the knowledge South Koreans receive at school and from mass media, we learn to reproduce a thicker boundary between North and South Korea. Yim Choon Sung (2009) states that among the many consequences South Korea faces due to our Americanization, one result is having university curriculums built to raise anti-socialism and anti-communism consciousness and forming hatred and refusal sentiments towards countries like North Korea and China. In the second half of the 20th century, our country’s scholars could not access materials and data from countries that the US had set as their ideological opponents (Kim, 2009). Our country’s body of knowledge, based on the data white intellects in the US provided since the 1950s, plays a significant role in shaping the perception of our country’s current students. The younger interviewees shared their South Korean school and university experiences as the following:

“As you know, we have a tendency in Korea to look down or to hate China. … Textbooks are the most important in Korean classrooms because they are the the FM 7 for everything. We get taught by rote at school and there is no room for questions or debates, so the textbook is important.” (H. Ryu, Personal interview, 18 February 2023)

“I had a university professor who was giving a lecture [in 2013], and he said to the students, ‘Our country is like a chess piece on the match America is playing.’ He was telling us how South Korea needs to move as the US directs us, like a puppet, like the military following orders. … there is a saying in Korea – when America sneezes, a tsunami hits our country.” (H. Kim, Personal interview, 25 February 2023)

“When I was in elementary school, I learned about the Sunshine Policy햇볕정책8. I remember seeing it in my textbook with the images of Kim Dae-jung and text about how he communicated with the leaders of North Korea to bring the two countries together. The teachers taught us the importance of the unification of Korea. … The notion of unification was still strong [in the early 2000s]. But there was none of that anymore in my middle and high school classes in the 2010s. Such contents were removed from the textbook, and the tone of describing unification completely changed. … People started talking negatively about unification. The teachers talked about the economic damage South Korea would have to face if we were to unite with the North.” (Y. Ha, Personal interview, 13 March 2023)

The closer South Korea stands to the US, the farther we get from the idea of unification with the North. My interviewees emphasized how it seems impossible to dream about a united future of the Korean peninsula anymore. Noam Chomsky says, “For South Korea, the major step has to be to move towards a peace treaty, as North Korea has been proposing and requesting for a long time. The US has been rejecting it. As long as there’s no peace treaty between the South and the North, South Korea is occupied” (JNCTV, 2023, 22:15). Our country used to focus on the divided families이산가족 with our country’s elders that have their lost bloodlines on the other half of Korea. Yet, through the recent years of depending so much on our alliance with the US, seeing the North as our enemies got prioritized. I look at my grandmother who has lived throughout the division – a condition that she and every Korean used to believe would be temporary but ended up becoming permanent.9 As I do my research and my practice, I wonder if Koreans would be able to see the undivided Korea again if I would ever be able to visit her old hometown and the beautiful mountain Keumgang금강산10 sitting right above the border.

My generation of South Koreans, who have lived most of our lives after the US began defining North Korea as part of their “Axis of evils,” have seen North Korea get labelled the “rogue state or threat to our national security in our country” instead of getting called as our neighbor, or the other half of us (Choi & Kim, 2021, pp. 31-70). While talking to my mother about how we feel emotionally connected with undivided Korea through my grandmother from Gyeseong (Appendix C), fear grew in me, thinking that the next generations of South Koreans may not see the need for the two pieces of Korea to come together again. What happens to us and the next generations, when these grandparents that call tell us about our lost half fade away? The younger South Koreans that are born now, and the ones to be born, would only access Korea before the division through text – text that gets altered every five years depending on the direction of our government What have we, South Koreans, earned from filling in our land with America in the past seven decades?

“Did you know we [South Koreans] are not allowed to talk to North Koreans even when we meet them outside our country by accident? It’s sad, isn’t it? We speak the same language, look the same, and we are all Koreans, but we are not even allowed to speak to them because any exchange with North Korean bodies is forbidden by law. That includes talking to them or even just saying hi. So even if you meet someone looking like you outside of Korea, you have to pretend you didn’t even see them if they are North Korean. … It used to be part of us. All of us. Yet it is the only place we are now forbidden from going to. There was that TV series from a few years ago with lovers separated by the border, remember? And the woman from the South says to her lover from the North something like, ‘People these days even go out to space, and yet you live in the one place I cannot go to.’

… And North Korea, by law, isn’t even our political enemy. We just see it that way because North

Korea and the US are opponents to each other.”

(K. Cho, Personal interview, 22 March 2023)

Conclusion

When beginning this research, I wanted to find out the force that makes South Korean bodies and minds move toward the US. Yet, I realized that through the Korean War and the following seven decades of rebuilding our country, it has never been a single force that formed South Korea’s direction toward America solid.11 It was not just the US, not just our conservatives or elites – it was myself, my interviewees, everyone in our country duplicating America within South Korea with each of our desires. South Koreans have suggested to each other the direction of going towards the US. We become each other’s directions and continue to make the direction thicker by putting our bodies in the flow.

In my research, I looked at how my home country’s closeness with the US affects the lives of South Korean individuals. Through discussing with other South Koreans, I realized how we are used to viewing America as superior to our country and in seeing the US and its influence during and after the Korean War as a support that helped us modernize. Such positive framing brings difficulty for South Koreans even to realize the cultural replacement and erasure in our country or our dependency on white American knowledge. Bell Hooks (1992) writes, “From what political perspective do we dream, look, create, and take action?” (p. 4) When American knowledge taught us, South Koreans – advancing happens by taking in American and Western influences because Korea with its traditions is incompetent – we learned to avoid and disdain our old culture and roots (Chung, 2005).12 Today, remaining silent is demanded in South Korea even when we see America exploiting our land, materials, knowledge, and people. Because we owe America support from the War, because we still have a lot to learn from America, because we need our alliance with the US to be safe from communism and the North. These narratives dance all over our country today, pushing away any thoughts that leave the boundary of America. But the more we get used to our closeness with the US, the further we drift from undivided Korea both politically and sentimentally.

Practice Project

나의 발이 바늘이 되어 보이지 않은 실을 달고쉼 없이 걷는 것.

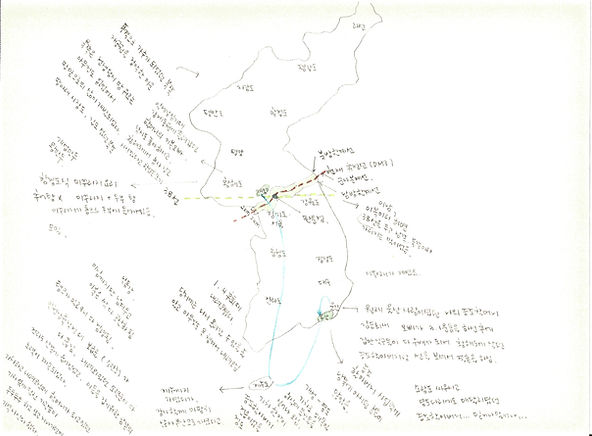

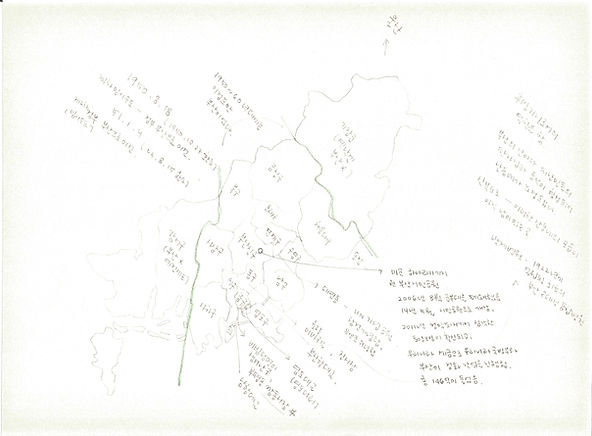

Through such findings, I created a practice work that brings light to the stories of my grandmother, who has lived throughout the division and kept the other half of her roots through the dishes from the North before the Korean War. While talking to my grandmother on the phone, I looked back at the years of Korea I read in my research through scenes my grandmother described. Her and her mother having to leave their home in Gyeseong in such a hurry that all they brought with them were a few pieces of jewelry wrapped in bojagi보자기13. Her walks, train, and boat rides through Jeolla, Ulsan, Yeongdo, Jeju, to Busan with her mother when she was 15. My hometown, Busan, that has tangible memories of the Korean War and the US military. How my grandmother has come to not think about the home or the rest of her family in the North, she could not go see anymore. But the dishes of the North she kept. The dishes my great-grandmother taught my grandmother and that my grandmother cooked for my mother and me. Through this research, I realized how the identity of Korea before the division (before the intervention of the US), which feels distant in academic articles, has been so close to me all this time. I put together the pieces of my grandmother’s memory of our lost half that she shared while teaching me her recipes for food from the North. My grandmother composed her dishes to keep a piece of Gyeseong; I compose her memories of the 1950s into a quilted bojagi보자기 to maintain my roots connected to the other half of the Korean peninsula that we miss. Through words and visuals that do not exist in textbooks or articles, I share the value of undivided Korea and of our identity that has been overlooked and forgotten over the years of Americanizing our land.

My grandmother used to tell me that Koreans see the act of building a house 집을 짓다, making clothes옷을 짓다, and dishes밥을 짓다 as practices of composing짓다 because all three of them require a lot of time and effort. What we compose with our hands over time shows our family and guests how much we respect, love, and care for them. I used to blame my grandmother for being very strict when raising her children. She constantly taught my mother, my aunt, and me that we should be able to prove ourselves being strong enough to survive in the world. But while talking to her and hearing about her life – through the Japanese occupation, the Korean War, and the division – I understood why she emphasized survival so much when we were young. My grandmother still has a habit of buying a new bag of 10 kilograms of rice before the old one reaches the bottom, having a mountain of eggs in her fridge, or always getting two or three bottles of soy sauce and oil. When I asked her why she does that, she told me – you never know. She did not finish her sentence, but I soon understood what she meant when in 2016, my friends in Korea told me they were stoking up their groceries because our news had been announcing every day about the tension between our country and the North rising very quickly and a local war seeming very close from breaking out. I realized that my grandmother had learned to prepare herself for another possible War – a situation that she never knew would happen and last so long, a situation that could break all parts of her life she had composed with time and effort within a few seconds. My grandmother wanted to train her children to be ready to stand strong even in loss and to be resilient to begin composing lives again – anytime, anywhere.

Would the 15-year-old me have known where her path of studying outside her motherland would take her? I kept questioning myself while doing this research, observing my home country and the lives of South Koreans around me. What have I been running towards all this time while spending two-thirds of my life walking towards the West that people in our country desire and see as our models and standards? Where have I been heading, without realizing how my dependency on American values and knowledge was adding to the direction of making my country drift far away from our independence and from finding the other half of us that we lost?

Paik Nak-Chung (1994, 1998) writes about how the unification of Korea can only be achieved under the continuous desire of the Korean public. I believe the direction towards our complete independence from America – both as a country and as individuals – is similar. It can only come true when we constantly think, wish, dream, and move together. So, I suggest my readers, especially South Koreans, pause and see where in the water we are floating right now with our minds and desires bound to America. To look back at how far all of us have paddled away from our roots before crossing the orange buoys. Towards what have we been flowing, and to where do we want to flow from now on?

금강산 찾아가자 일만이천봉

Let us go find Mt. Keumkang, with 12,000 tops

볼수록 아름답고 신기하구나

The more we see it, the more beautiful and interesting it is 철 따라 고운 옷 갈아입는 산

A mountain that changes its clothes every season 이름도 아름다워 금강이라네

Even the name is beautiful – a mountain called Keumkang

금강이라네

Mountain called Keumkang

금강산 보고 싶다 다시 또 한번

We wish we could see Mt. Keumkang once again

맑은 물 굽이쳐 폭포 이루고

The clear water meanders to create a waterfall 갖가지 옛이야기 가득 지닌 산

A mountain that carries all kinds of our old stories 이름도 찬란하여 금강이라네

Even the name is brilliant – a mountain called Keumkang

금강이라네

Mountain called Keumkang

– Lyrics of “Keumkangsan” song

(May 3 2023 Interview Transcript, Appendix B)

Footnotes

https://www.towheredoweflow.com/what-are-portals-in-korea

Reference List

Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press.

An, S., & Suh, Y. (2013). Simple Yet Complicated: U.S. History Represented in South Korean History

Textbooks. The Social Studies, 104(2), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377996.

2012.87410

Brantner, C., Lobinger, K., & Wetzstein, I. (2011). Effects of Visual Framing on Emotional Responses

and Evaluations of News Stories about the Gaza Conflict 2009. Journalism & Mass

Communication Quarterly, 88(3), 523–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/

107769901108800304

Bucher, H.-J., & Schumacher, P. (2006). The relevance of attention for selecting news content.

An eye-tracking study on attention patterns in the reception of print and online media.

Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research, 31(3), 347–368.

Cha, J. (2018). The U.S. Specialist Program for Korean Journalism in the 1950s. Korean Journal of

Communication & Information, 87, 243-276.

Cho, J, Lee, J. S., & Song, B. K. (2017). Media Exposure And Regime Support Under Competitive

Authoritarianism: Evidence From South Korea. Journal of East Asian Studies, 17(2),

145–166. https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2016.41

Choi, B. (2023, March 18). 대일 굴욕 외교 규탄 대회 [Speech audio recording]. MBC.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eIZ380btZy4

Choi, J. & Kim, S. (2021). 국제권력질서와 담론정치: 한미 언론의 ‘북한 악마화’ 담론을 중심으로.

정치커뮤니케이션연구, (60), 31-82. KCI.

Choi, S. (2023, April 11). South Korea says leaked US intel document “untrue”, amid spying

allegations. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/pentagon-chief-vows-

cooperate-with-south-korea-following-us-intel-leak-report-2023-04-11/

Chung. I. (2012). American Empire and ROK: Beyond ROK-U.S. Relationship. 사회와 역사. (96),

113-150. KCI.

Chung, I. (2005). Americanization of Social Science Paradigm: The Dissemination of Modernization

Theory and Its Reception in South Korea. Journal of American Studies, 37(3), 66-92. KCI.

Chung, I. (2007). Articles: Korean Democracy and America: American Intervention in the Korean

Politics through Overt Means and through Non-Intervention during Park Chung Hee Era.

Memory & Future Vision, 17, 202-238. KISS.

Do, K. (2018, January 4). [사진오늘] 한강 앞에서 우는 어린이들, ’1.4 후퇴’의 비극. 연합뉴스 Yeonhap News

Agency. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20180103164200013

Gibson, R., & Zillmann, D. (2000). Reading between the Photographs: The Influence of Incidental

Pictorial Information on Issue Perception. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly,

77(2), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900007700209

Hamad, L. (2018). A Language Split by the Border [Review of A Language Split by the Border].

Harvard International Review, 39(3), 22–25.

Han, J. (2021). A Preliminary Study on the Relationship between South Korea’s Transition to A

20

Country of Immigration and the Regime of Division in the Korean Peninsula. Korean

Journal of International Migration, 8(2), 102-118.

Hooks, B. (1992). Black Looks : Race and Representation. Routledge.

Jung J. (2019). [따옴표 저널리즘의 딜레마] 관행이란 이름의 범속함, 그 악의 평범성. 방송기자, 47(1), 12-14.

Jung, J. “[해시라이브6회] 흐려버린 기억 속에 선명한 국가 폭력의 역사.” Www.youtube.com,

HASHTV, 6 Apr. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=4_rIT4_47vY&t=5856s. Accessed 24

Apr. 2023.

Jung, J. “[해시라이브 9회] 국제관계와 국내정치, 국익방출 국빈방문.” Www.youtubecom,

HASHTV, 27 Apr. 2023, www.youtube.com/live/Uw2Aa1wBr84?feature=share.

Accessed 15 May. 2023.

JNCTV. (2023, May 11). (Apr 26) An Evening with Noam Chomsky: The Korean Peninsula and

the US Drumbeat to war in East Asia. Www.youtube.com.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MWd7G42-uHs

Kang, B. (2021, February 27). [논설위원의 뉴스 요리] 부산 서민들의 공간 산복도로를 가다. Busan Ilbo.

https://www.busan.com/view/busan/view.php?code=2021022509295426986

Kern, T. (2005). Anti-Americanism in South Korea: From Structural Cleavages to Protest. Korea

Journal, 45(1), 257–288. Korea Citation Index. KCI.

Kim, D. (2005). Consumption and the Question of the Americanization in Korea since 1945. Journal

of American Studies, 37(3), 156-189. KCI.

Kim, N. (2022, October 19). 尹대통령 “北따르는 주사파…反국가 세력과는 협치 불가능”(종합). Yeonhap News.

https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20221019139851001

Kim, O. (Host). (2023, March 21). 김어준의 겸손은 힘들다 뉴스공장. Podbbang.

https://www.podbbang.com/channels/1787095/episodes/24663444

Kim, S. (2022). From Portal to Mega-Platform. Media & Society, 30(1), 252-275. KCI

Kim, Y. (2005). America and Americanization: Images and Discourses as Revealed in Korean

Journalism. American Studies, 37(3), 7-38. KCI

Kim, Y. (2009). A Reevaluation of Dr. Syngman Rhee’s Role in the Process of Founding the Republic

of Korea. Korean Political Science Review, 20(2), 107-127. KCI

Korea Daily. (2017, January 4). 1.4후퇴. 한국일보 Korea Daily. https://hankookilbo.com/News/

Read/201701040414571249

Lee, J. (2016). Presidents’ visual presentations in their official photos: A cross-cultural analysis

of the US and South Korea. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 3(1).

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2016.1201967

Lee, J., Han, M. W., & McKerrow, R. E. (2010). English or perish: how contemporary South Korea

received, accommodated, and internalized English and American modernity. Language

and Intercultural Communication, 10(4), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.

2010.497555

Lee, Y. (2020). American Material Culture in early Modern Korea: Advertisements of American

Products in Korean Newspapers (1890-1910). Journal of American Studies, 52(3), 91-116. KCI.

Lo, A., & Chi Kim, J. (2012). Linguistic Competency and Citizenship: Contrasting Portraits of

Multilingualism in the South Korean Popular Media. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 16(2),

255–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2012.00533.x

Mcleod, D., Wise, D., & Perryman, M. (2017). Thinking about the media: a review of theory and

research on media perceptions, media effects perceptions, and their consequences.

Review of Communication Research, 5, 37–83. SSOAR.

https://doi.org/10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2017.05.01.013

National Archives. (2008). National Archives. Archives.gov. https://www.archives.gov/

National Archives of Korea. (2004). National Archives of Korea. Www.archives.go.kr.

https://www.archives.go.kr/next/viewMainNew.do

Ng, C. (2022). Our Missing Hearts. Penguin.

Oh, J. (2013, July 27). 부산에서 가장 부산다운 곳 “초량 이바구길.” Www.korea.kr.

https://www.korea.kr/news/reporterView.do?newsId=148760882

OhmyNews. (2018). 1951. 1. 강추위 속에 끝없이 이어진 1.4 후퇴 피란행… – 오마이포토. M.ohmynews.com.

https://m.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/Mobile/img_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=

IE002292118&atcd=A0002408382

Olsen, E. (1990). ENDING THE COLD WAR IN KOREA. The Journal of East Asian Affairs, 4(1), 22–43.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23253531

Paik, N. (1994). 분단체제 변혁의 공부길. 창작과비평사.

Paik, N. (1998). 흔들리는 분단체제. 창작과비평사.

Shim, D., & Flamm, P. (2012). Rising South Korea: A Minor Player or a Regional Power? SSRN

Electronic Journal, 200. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2143127

Shin, G. (1996). South Korean Anti-Americanism: A Comparative Perspective. Asian Survey, 36(8),

787–803. https://doi.org/10.2307/2645439

Uhm, G. (2011). 뿌리깊은 미국 사대주의 그대로 드러나 국정조사로 진실 밝히고 관련자 문책 필요.

민족21. 76-79.

Yim, C. (2009). The Americanization of Korean Universities and Their Perception of China. The

Journal of Modern China Studies, 11(1), 291-320.

Yun, S., & Chang, W. Y. (2011). New Media and Political Socialization of Teenagers: The Case of the

2008 Candlelight Protests in Korea. Asian Perspective, 35(1), 135–162. https://doi.

org/10.1353/apr.2011.0019

Appendix A

Table of In-depth Interviewees

Between 14 February and 15 May 2023, one-on-one 45-60 minutes long interviews

were held every two weeks, and 45minutes long group conversations were held every 5-6 weeks.

(Notes translated from Korean to English)

– My grandmother went from Seoul to Jeolla, Jeju, Ulsan to Busan; she said that my great-grandmother was looking for a city where she could make a living by opening a business that she went through all the cities in the South until she settled down at Busan.

– The area Sanbokdoro (meaning roads on the mountain in Korean; Busan is a city named after having many mountains) was crammed with many Koreans that fled from all regions of Korea in the 1950s. My grandmother described how the temporary capital of the South used to be in Busan because that was the only land that the Soviets had not occupied at the peak of the Korean War.

– Apparently, the dishes up in the North got a lot of influence from China or the region of old Manchuria, especially in the way dump-lings or dishes with ducks and porks are made.

– Up in the North, the Hwanghae region was the only place that had flat lands where people could harvest rice. My grandmother told me that her family, before the Korean War, had a surplus amount of materials all the time and that having rice was not difficult, but usually, rice in the North was only found in the Hwanghae region. People in the North did not have rice cakes because they did not have enough rice compared to the South. Buckwheat was more commonly harvested in the North. Wheat did not grow in the North, so dishes depended a lot on starch (from corn, potato, or sweat potato), especially the noodles. Naengmyeon, which is a cold noodle dish that Koreans have in the summer, apparently is a name that South Koreans put. The weather in the North was a lot colder than in the South, so it was more convenient for Koreans living in the North to make a broth and leave it outside for just a few hours, which would turn into a slushy icy soup rather than trying to make a hot noodle dish all the time. Today in the South, this gets sold with the name Hamhung (a region in the North) naengmyeon. But in the North, it was just noodles.

– My great-grandmother had a stepbrother that participated in

the March 1st independence movement back when Korea was colonized by Japan. My grandmother said that the entire family

in Ulsan had been blacklisted by the Japanese police, and my great-grandmother ran away as far from Ulsan as possible. In a way, she was trying to leave her identity in Ulsan to be safe; she met my great-grandfather up in Hwanghaedo and married him.

– My great-grandfather was a chief carpenter and built houses until the War happened, which used to make a lot of money in Korea back then. Grandmother said that he had a whole unit of a train that would carry timber when going down from Gyeseong to Busan and would bring back all kinds of fish and seafood from Yeongdo (right next to Busan) on its way back to Gyeseong. My great-grandfather once had fought with a cow and had hung on the tip of the Yeongdo bridge just with his hands when the bridge opened, and he missed the time to leave the bridge…believe it or not.

– My grandmother came down to the South with her mother during the January Fourth Retreat; she said she and her mother didn’t bring a lot with them when they left Gyeseong because they believed they would return home soon.

– She remembers how the riffles attached to the train she took from Seoul to Jeolla sounded really loud; she described that the train stopped when passing the mountains in Jeolla and transformed into a weapon to shoot at the Soviets that were hiding in the mountain. She was 15 when she was on that train with her mother.

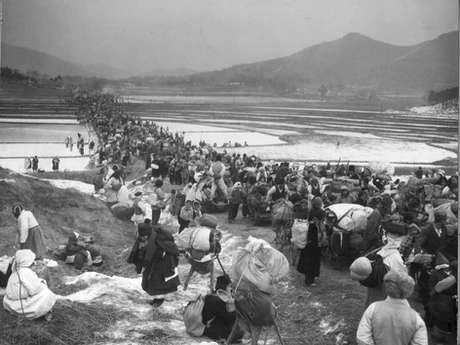

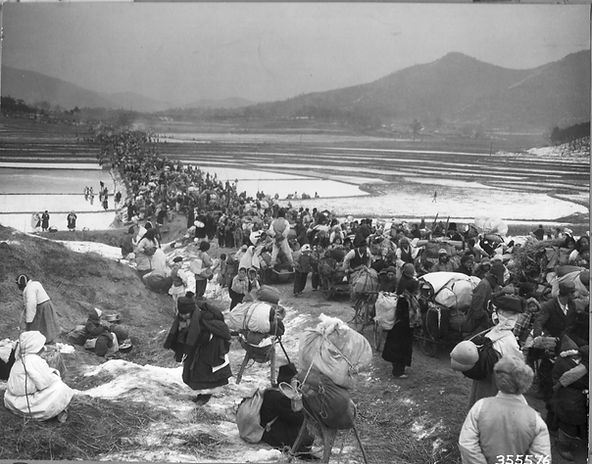

Image 1 (above). Rows of Koreans departing Seoul to flee to the South in January 1951 as soon as Seoul, the capital of Korea, gets occupied by the Soviets. Source: US National Archives and Records Administrations

Image 2 (below). Mother carrying her child on her back and belongings her head, wrapped in bojagi보자기 during the Korean War. Source: National Archives of Korea

Image 3 & 4 (above ). Making Gyeseong man-du개성만두 (dumplings in Gyeseong style) with my grandmother

Image 5 & 6 (left and below). Gyeseong man-du개성만두 on my textile quilt next to notes of my grandmother’s recipe

Map 2 (above). Map of Busan I drew while calling my grandmother to understand her route of travel and the relation of my hometown with the US military bases and the tin can open market in Busan.

Image 7 (below). Photo of Sanbokdoro (roads on the mountain) in Busan, Dong-gu, taken in 1960. This area, which has been my family’s hometown for the past seven decades, got crammed with Korean refugees coming from all regions of Korea during the Korean War in 1950. Source: Busan Ilbo (2021).

Image 8. Keumkangsan-do금강산도 from the Lee Kun-hee collection exhibited at Daegu Museum in South Korea, spring 2023; The Mountain Keumkang sits right above the DMZ border line Koreans in the South last had access to the landscape before the Korean War. The divided Korean families met each other around this mountain in the late 1990s and early 2000s during the two consecutive liberal administrations’ Keumkangsan Tour project, which was a part of the Sunshine policy햇볕정책.

Community.