The de-radicalisation of Jazz hurts the DRC till this day. I sat down with Lizmnk, a singer-songwriter from the Congolese diaspora and Aleria, a violinist-singer and British Nigerian.

What is the end goal of a musician ? Fame, glory, recognition for all the hours spent to create compositions that will stand long after we leave our bodies. As a developing artist in the London Jazz Scene – the career trajectory looks like..

The career pathway sounds exciting but how do you hold your community ?

One cold Sunday afternoon, at Ritzy Cinema in Brixton – I watched the groundbreaking documentary Soundtrack to the Coup D’Etat. Even though I learned about DRC in the Black-led Saturday schools. The doc starkly reminded me I hadn’t rectified my complicitness with the extraction of Congo (DRC). In search of exploring ways in which I could be decolonial as an artist – I sat down with Lizmnk, singer-songwriter from the Congolese diaspora and Aleria, violinist-singer from the Nigeria Diaspora.

Soundtrack to the Coup D’Etat doesn’t hold back at the extent of the violence faced by children and people of the DRC. Lizmnk grew up going to protests with family members and witnessed on screen the genocide her parents fled. The film “was deeply painful to watch”, “for a long time it felt like we were screaming into the void”. The doc explores the role of Jazz musicians being used to distract from the CIA’s role in the genocide of Congo (DRC) and the assassination of Patrice Lumumba.

All three of us recognised that Black Jazz Musicians were tricked into “using a Black Art form” for Empire to quote Aleria. For many Jazz musicians the tours were the “first time (Black Musicians) were being recognised, uplifted and platformed internationally” in the midst of Jim Crow, Lizmnk reflects.

One vivid scene Aleria recalled was Louis Amstrong’s revulsion on learning how he was used. Amstrong threatened to renounce his US Citizenship for a Ghanaian one. Abbey Lincoln, who also featured in the film, protested the assassination of Lumumba by interrupting the UN general assembly with Maya Angelou and fellow activists, using her vocal chords to stand up to power.

Louis Amstrong’s and Abbey Lincoln’s repulsion demonstrates the necessity of not being ignorant about Jazz as a political tool. The heart of Jazz is Congo Square, (now located in Louis’ Armstrong Park) – a place where enslaved people gathered, shared mutual aid and “continued practices .. from their homelands” (New Orleans Jazz Museum, 2022). Congo Square and DRC are bound together, beyond a shared name – both people had been used by the US and allies to sever their relationships to their indigenous lands for racial capitalism.

Every Jazz lover should know about the role of Congo Square, but sadly omission in academic texts dilutes Jazz’s spiritual power (Bolin, 2024). We desperately must steward the legacies of Black music by “recognising when our sounds are manipulated to suit a western audience – as we can lose what made that music our music.” – Aleria shares. In knowing the histories of our music – we must not treat Pan-africanism as an aesthetic to use for our own profit. Pan-africanism has a rich political history that seeks the end of coloniality. In the film, we hear how Congolese musicians crafted music to celebrate independence from Belgium.

Decolonisation is not a metaphor

“Decolonial feminism holds a multidimensional analysis of oppression and refuses to divide race, sexuality and class – and has a shared goal of re-humanising the world” – “that are linked to anti-capitalist and anti-imperial struggles” (Verges, 2021).

Social media has enabled a lot of us to learn more about DRC and has become “trendy” as Lizmnk highlights. It might be easy to think slacktivism is organiing but anti-imperialism has never been comfortable.

Adopting a decolonial feminist analysis of how we generate revenue and align ourselves with brands is foundational. “Decolonisation is not about making the face of the industry Black, it’s about the context”, Lizmnk expands. Far too often, we can jeopardise decolonial organising by usurping the term for just wanting a better seat on the dining table of racial capitalism (Uncharitable, by JMB Consulting, 2023).

Aligning ourselves with companies like Amazon, Spotify and Apple, who increasingly take a role in sponsoring creativity as a band aid in the face of enshittification of social media platforms is unsustainable (Shepeard, 2024). In the west “we consume way too much.. as much as music technology has opened doors for artists to work outside of the label structure”. “The resources and freedom to create comes from the blood of people ….the invasion of Goma is directly linked to our overconsumption” Lizmnk shares.

In building fan bases, creating albums, going on tour – so much of the infrastructure we rely on uses minerals from Congo. “We need to start stripping down things that aren’t important” as well as “holding companies to account”, Lizmnk shares. Stripping things down might start with diverting money we spend on entertainment and technology to urgent calls for donation by the Friends of the Congo. We can also prioritise second-hand technology as part of a cyclical economy, Lizmnk shares. Artists can also refuse to perform for organisations complicit in the extraction of DRC (Congo Friends, 2024), especially if their platform is substantial.

How can we radically organise, if we don’t even support our neighbours ?

Divestment is more difficult for working class folks as the streaming era has sadly made artists more dependent on brand partnerships for revenue. Not having a safety net of community reduces our capacity for resistance. By holding both the necessity for folks disposed within the west, we can also extend to solidarity with anti-colonial struggles.

We can learn from Care Erotics of Liberation, who is building a We Care Fund, for Black & Queer folk who struggle to pay rent and have food. We Care fund is generated through resources Care has crafted to build the social skills needed to become abolitionists. Care demonstrates how we can build capacity for folks and has used their platform to highlight the Apple boycott (Care of Liberation).

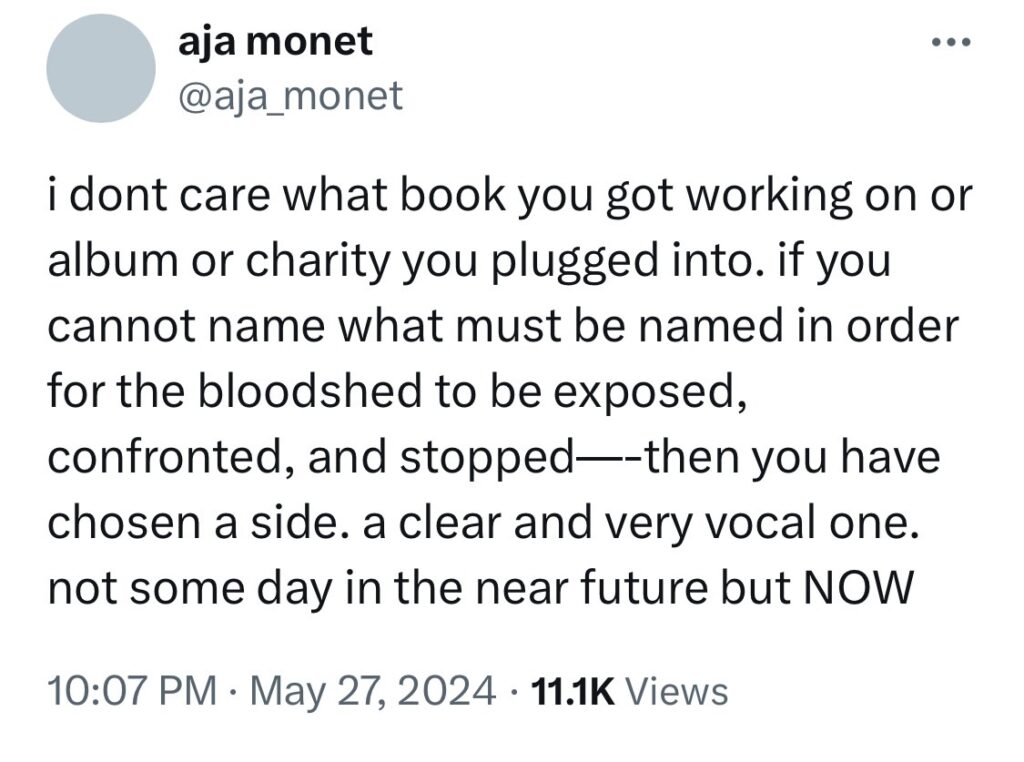

Artists forge the lenses of culture, we can’t stop at just watching the film. “All that organising strength you be using for your own personal projects – use that to rally to put an end to genocide”, Aja Monet urges all of us.

Community.