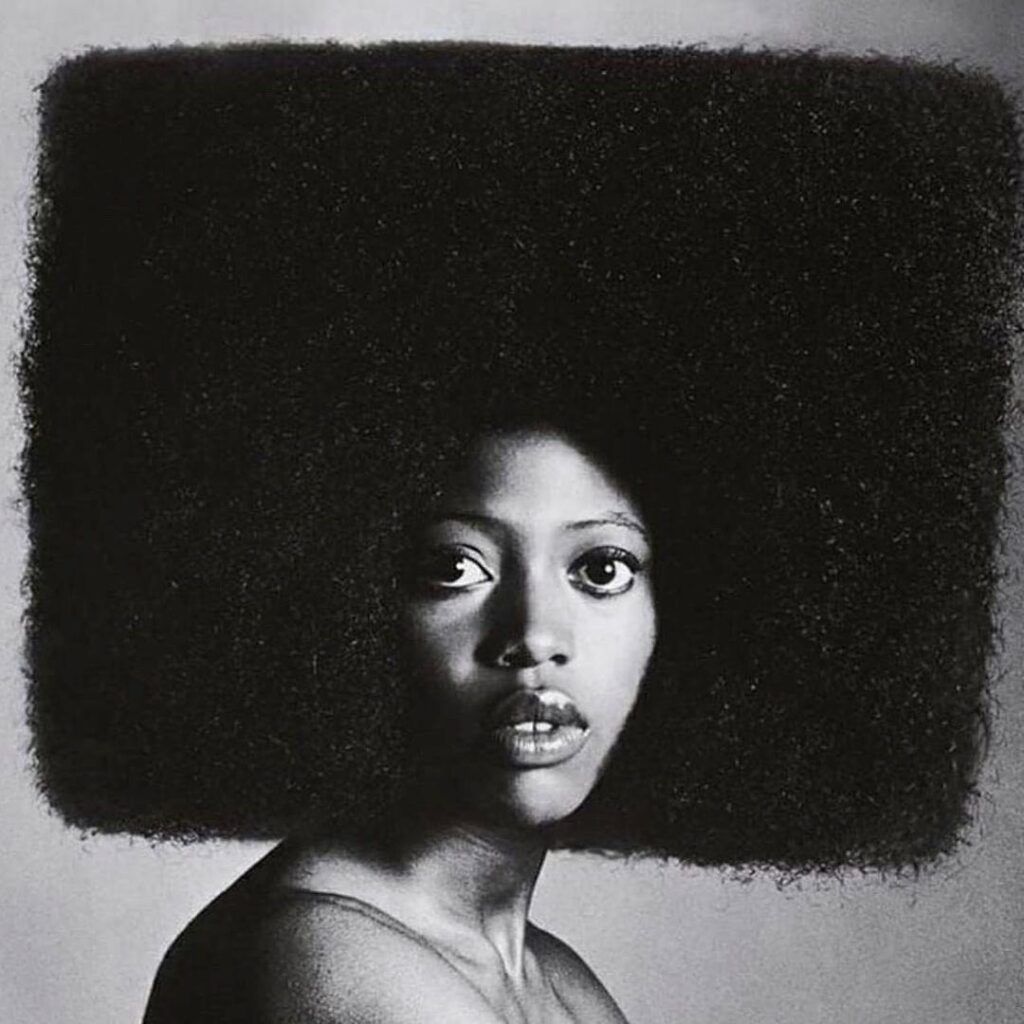

It takes courage to be seen as you are, to decolonize beauty, when the world tells you to hide your roots.

In Latin America, beauty has never been neutral. For Black and Afro-descendant women in particular, the pressure to chemically straighten or flat-iron natural curls is more than aesthetic. It’s racialized. It’s gendered. It’s deeply colonial.

“I used to reject that part of myself [curly hair]. I even used a clothes iron once to straighten it, and I burned myself. I thought straight hair meant ‘neat,’ ‘elegant,’ ‘professional,’” said Stephanie Campos, co-founder of Encolochadas, a Salvadoran digital community dedicated to curly hair and cultural healing.

From schools to offices, from family gatherings to media representation, natural Black hair is often cast as “messy,” “unprofessional,” or even “ugly.” These judgments aren’t random, they stem from centuries of white supremacy that positioned whiteness and its aesthetic features as the “ideal.” Straight hair was framed as clean, desirable, and modern. Textured, coily, or kinky hair became everything else: “unattractive and undesirable.”

“Hair is political for Black women in the sense that we are probably the only people in the world who are expected to change the hair that nature gave us in order to fit what is called the ‘mainstream ideal’,” said Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in an interview for The Economist (2020).

In Brazil, the expression “cabelo ruim”—bad hair—is still part of everyday vocabulary. It doesn’t refer to hair health, but to its texture: kinky, coily, natural Black hair. The word “bad” is not descriptive; it is deeply colonial and racist.

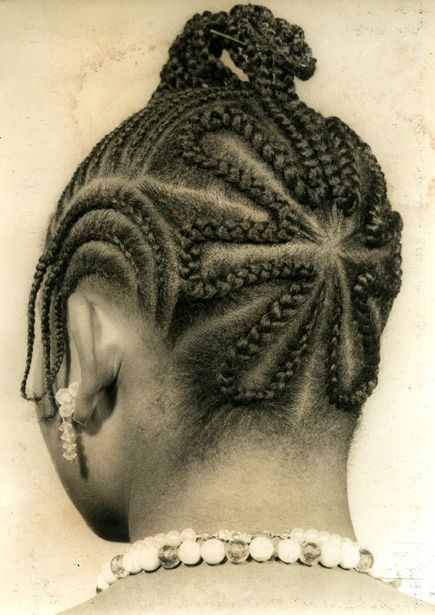

Dr. Luane Bento dos Santos, a Brazilian sociologist and professor at Fluminense Federal University in Rio de Janeiro, calls this aesthetic colonialism an act of epistemic violence. “Braids and textured hairstyles are not just trends,” she explains. “They are cultural affirmations rooted in ancient African civilizations.”

Her research shows how traditional African hairstyles carried meaning and function long before European colonizers set foot on the continent. “In the Himba civilization, braids marked life stages from childhood to adulthood. In Yoruba traditions, hair is sacred. Priestesses wear specific styles to honor deities like Oxum and Iansã,” she said. “In the diaspora, these hairstyles have been re-signified, reborn as symbols of resilience and community.”

To see cornrows or box braids merely as aesthetic or trendy, Dr. Santos argues, is to erase a lineage of cultural resistance, political memory, and embodied pride. Hair, in this sense, becomes a living archive of Black history.

She emphasizes that decolonizing beauty also means not hierarchizing bodies, skin tones, facial features, or hair textures. “There are specific haircare technologies that were developed for kinky and coily hair, braids, locs, bantu knots,” she explains. To honor this diversity is to treat it with dignity. “It’s also a call for an inclusive beauty industry that reflects and serves this diversity”, she adds.

For centuries, whiteness was upheld as the universal ideal of beauty, blue or green eyes, straight blond hair, and light skin. “Black girls, growing up without representation, internalized rejection. The few who were accepted were those with features closer to whiteness. The rest of us were taught to disappear”, Dr. Santos shares.

This rejection becomes physically manifest. Brazil has one of the world’s highest rates of rhinoplasty, and notably, many Black Brazilians, upon achieving social mobility, feel pressured to undergo the surgery as a means of distancing themselves from visibly Afro-descendant features. Dr. Santos highlights that this is not a coincidence:

“It’s the violence of trying to cut away your Blackness. This widespread demand for nose reshaping is directly tied to a deep-rooted rejection of Black features and the colonial ideology that to be successful, respectable, or beautiful, one must assimilate to whiteness.”

This ideology doesn’t stop at facial features. Across Latin America, the Caribbean, and much of the Global South, skin lightening remains a multi-billion-dollar industry, aggressively marketed to Black and Brown communities. Despite well-documented health risks, including mercury poisoning, millions continue to use whitening creams in pursuit of a Eurocentric ideal.

“It’s not vanity,” Dr. Santos notes. “It’s survival under a system that teaches us lighter is safer, more employable, more lovable.” From filters that digitally lighten skin to influencers endorsing “tone correctors,” the pressure to assimilate is both systemic and deeply personal.

In her doctoral thesis, Dr. Santos introduces the concept of racismo estético—aesthetic racism—a term that connects colonial beauty standards with mental health, environmental harm (due to toxic beauty products), and bodily autonomy. She also underscores how these pressures disproportionately harm the self-esteem and health of Black women, beginning in childhood and reinforced through media, education, and beauty industries.

I still remember the first time I tried to transition to natural hair. I had endured years of chemical straightening, scalp burns, and the suffocating smoke of salon treatments. I remember once sitting under a dryer while others laughed at my discomfort, as if pain were a rite of passage. But it wasn’t a joke. It was violence masked as beauty.

Marina Mateus, a Brazilian clinical psychologist, describes a similar experience. “I started straightening my hair as a teenager. “It was only during the pandemic that I decided to stop. At first, it was hard. But then it felt liberating. I could swim. I could sweat. I was no longer a prisoner to the flat iron.”

But for her, like for many of us, the transformation went deeper.

“I always saw myself as ‘parda’, mixed-race, not quite Black, not quite white. But caring for my natural hair, learning about its history, helped me see myself as a Black woman,” Marina said. “It’s still a process. But I would never go back.”

As a psychologist, Marina sees firsthand how beauty norms shape mental health. “Self-image is built early. If the world tells you your hair is ugly, you internalize that,” she explains. “I’ve seen girls cry over their curls. But I’ve also seen them heal when they finally see themselves reflected in the world around them”.

For Black girls beginning their transition to natural hair and feeling uncertain, Dr. Santos emphasizes the importance of seeking out professionals who specialize in caring for coily and kinky textures, those who don’t promote straightening or relaxing as the only path to beauty. But transitioning is more than a cosmetic change; it’s also deeply political.

Drawing on the work of anthropologists Larisse Pontes Gomes (2017) and Denise Cruz (2017), Dr. Santos reminds us that hair transitions represent a shift in perception about one’s body, identity, and value. She encourages reading books, articles, and watching documentaries by Black filmmakers and collectives. “We must transition not only our hair, but our racial consciousness,” she says. Knowledge of African history, culture, and race relations acts as both preparation and protection, a shield against racism and a foundation for self-esteem. “It’s not just about lifting our curls, but also lifting our minds.”

The transition to natural hair often brings profound emotional challenges, especially related to self-esteem. Marina reflects, “I was considered pretty with straight hair and ugly with curly hair… I internalized that deeply.” She describes the process as a difficult yet necessary journey of confronting internalized beauty standards and reshaping self-image. “One of the most important parts is changing how we see ourselves, learning to undo the belief that we are less beautiful just because we don’t fit into dominant ideals.”

Stephanie Campos and Bea Mar launched Encolochadas not just to talk about curls, but to spark healing. Their Instagram page quickly became a space of testimony, sisterhood, and political consciousness.

“We were tired of hiding,” Stephanie says. “People told me I looked unkempt or less feminine with curly hair. I started straightening at 12; it was what everyone did.” But hair loss, scalp damage, and stress led her to stop. What she found instead was pride. “Curls are not dirty. They are powerful.”

They chose the name “Encolochadas” from colocho, a Salvadoran word for curls with Indigenous roots. Their mascot, Zuri Encolochada, is a joyful Black girl with big curls and bigger confidence, a rare image in Central American media.

“To wear our hair as it grows is a political act,” Bea says. “We’re telling the world: we are enough, just as we are.”

Healing from beauty-based violence is not a solitary act. It is a collective journey, and community is the ground where that healing becomes possible.

In Brazil, Dr. Santos reminds us that Afro beauty salons, blocos afro, and Black-led cultural spaces are more than just aesthetic environments. “They are ‘safe spaces’ where Black people can talk, cry, heal, and remember they are not alone,” she says. This perspective draws on the work of sociologist Patricia Hill Collins, who, in her book Black Feminist Thought (2019), describes Black beauty salons as crucial safe spaces within Black communities. “In my research, I found that trançistas [braiders] are not just stylists. They are therapists, cultural educators, and emotional anchors.”

In a context where psychology and psychiatry still struggle to recognize race, gender, and class as fundamental categories for understanding trauma and mental health, these salons become sanctuaries of listening, identity, and resistance.

“Psychology and psychiatry often fail to recognize racism as trauma,” Dr. Santos explains. “But community spaces created by and for Black people do. They affirm dignity, identity, and resistance through daily acts of care.”

Encolochadas, the Salvadoran platform launched by Stephanie and Bea, is one of these powerful community spaces. Though virtual, its impact is deeply real. What began as a beauty pageant became a liberation movement.

“Our page became a place where people could share their stories, post their selfies, and find others who were going through the same process of unlearning shame,” said Stephanie.

The physical toll of conformity is real. A 2020 study published in the International Journal of Cancer found that Black women who used chemical straighteners were significantly more likely to develop breast cancer. A 2023 study linked frequent straightener use to a doubling of uterine cancer risk.

“It was making me sick,” Stephanie said. “And still, people told me: ‘It’s just hair.’ But it’s not. It’s health. Its identity. It’s survival.”

Beyond health risks, the emotional damage is equally alarming. According to research by Google BrandLab in Brazil, one in three women has experienced discrimination because of their hair, and four in ten have admitted feeling ashamed of their curls. Among young women aged 18 to 24, only 24% even recognize their hair as curly, a statistic that reveals just how beauty violence becomes internalized.

Every curl is a revolution

To transition is not easy.

It means confronting shame.

Unlearning violence.

Standing tall in a world that tells you to shrink.

But it’s also a radical act of love. Of reclamation. Of defiance.

“Changing our internal self-image, confronting the idea that we’re ‘ugly’ by white standards, is one of the hardest things,” Marina Mateus said. “But it’s also the most necessary.”

Because hair is not just hair.

It is memory.

It is culture.

It is political.

Choosing to straighten or style your hair is valid, but what must be questioned is why that choice often feels like a necessity rather than a preference.

As Audre Lorde reminds us in A Burst of Light: and Other Essays (1988), “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence. It is self-preservation. And that is an act of political warfare.”

And so every twist, every braid, every liberated curl becomes a strand of rebellion.

We are not just changing our hair.

We are decolonizing beauty itself.

Community.