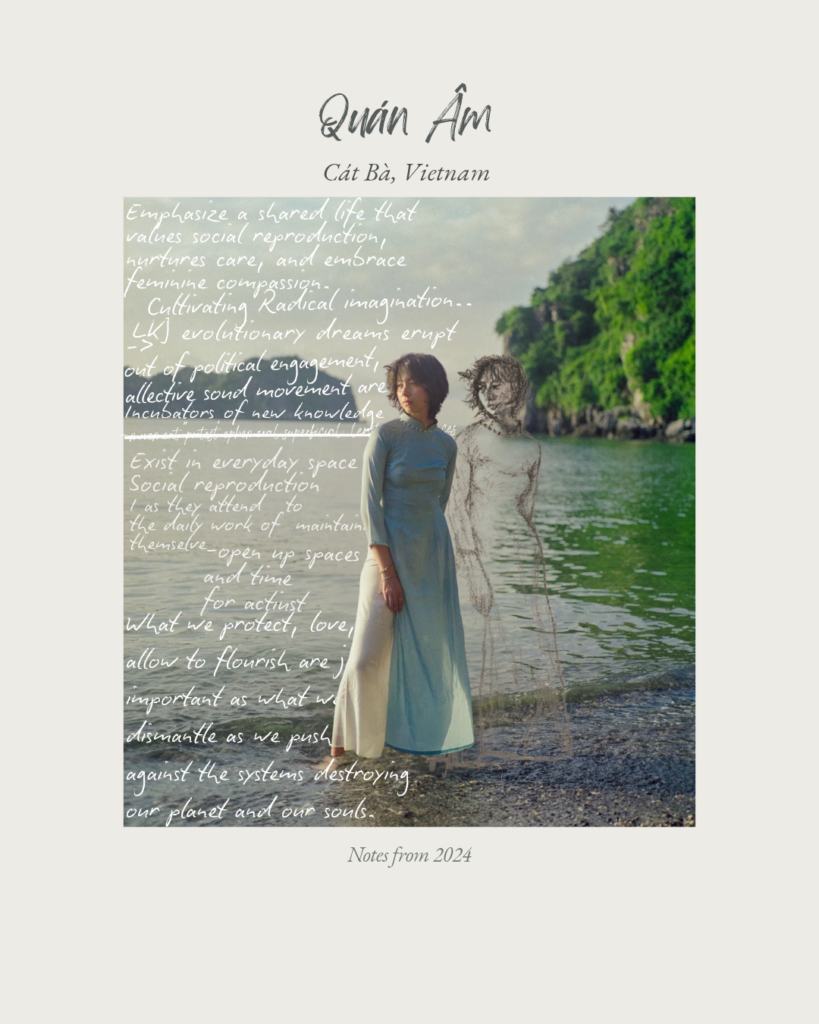

As I distance myself from colonial, traditional depictions of femininity,

The charming woman, captivating, yet transcendent of her shallow past.

She descends from Thebes, Crete, Chichén Itzá, Quan Âm

A totem, an animal, dehumanized and othered.

My body, a battlefield,

Mapped by colonial hands, reshaped by colonial gazes.

A half-forgotten story etched in flesh,

Half-colonized, half-colonial, never whole.

They sculpted the “charming woman,”

A myth, a mask, a body adorned in beauty, yet stripped of power.

A commodity woven from silk and suffering.

Femininity redefined,

From fluid, free form to rigid, binary chains.

Tamed, trained, extracted, exploited.

I anguish: can such fleeting beauty justify the harm it endures?

If it demands blood or suffering, it must be relinquished.

Men have reached for her, but she vanishes

The daughter, the lover, though they speak like others,

Her words and body are no longer burdened by imposed weight.

Beneath her garçonnet hair, the whispers of the forest transform into thought,

Allowing her voice to flow effortlessly.

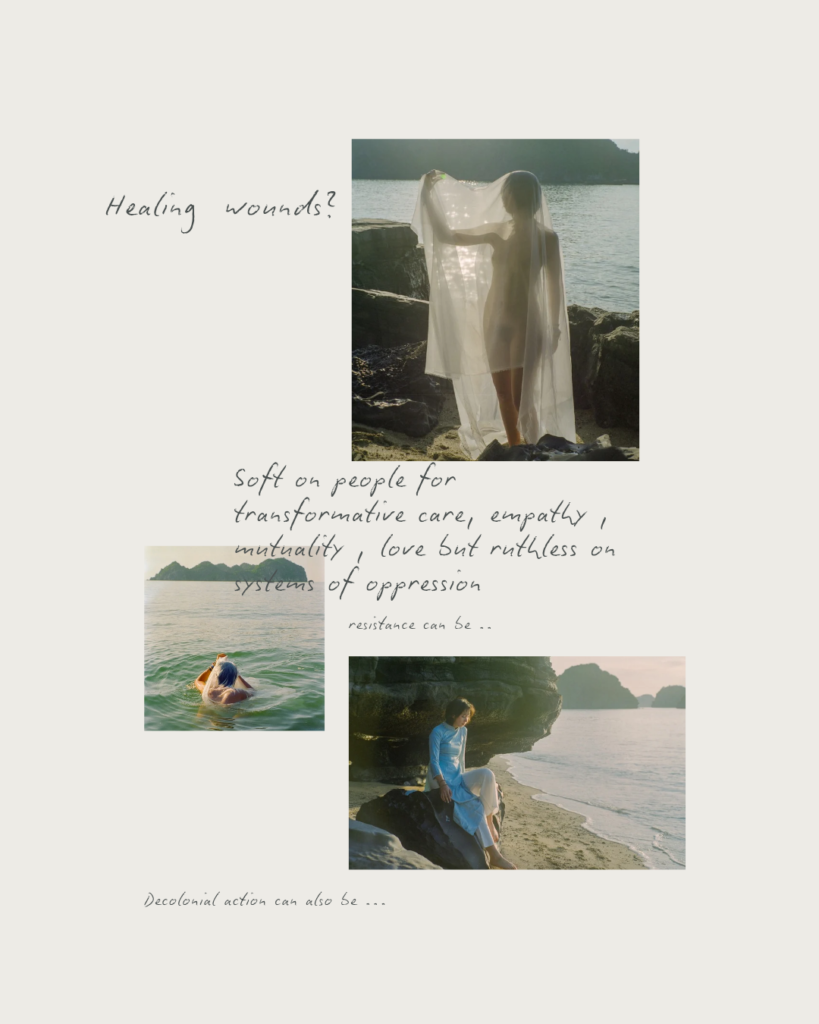

Do I sacrifice my body again to resist,

Or do I reclaim it?

Releasing the safety net of the little girl behind her delicate brushstrokes,

I discover my voice.

The charming woman transforms

Becoming something modern, something masculine, something brash.

But will it be at the cost of losing the essence of that femininity within myself?

Or could it mean radically existing beyond a femininity so easily commodified, Manipulated, sexualized, and overvalued to be exploited?

To radically resist coloniality that seeps through the everyday

Is to claim self-determination,

Over my body, my voice, my relationship with the Earth.

To reshape the way I exist.

The whispers of Thebes, Crete, Chichén Itzá, Quan Âm

Still hum beneath the surface,

Calling for reclamation, for rupture, for rebirth.

I refuse to be their myth.

I refuse to be their tool of control.

This body is mine.

This story is ours.

This fight is forever

Analysis of the Female Body as a Battleground Against the Colonial Gaze

Colonialism has shaped how we perceive, regulate, and exploit the female body. The image of the “charming woman” is not just aesthetic; it is a constructed tool used to commodify and control femininity. Behind this beauty lies a history of violence against racialized women’s bodies: unpaid labor, economic extraction, and sexual coercion.

As Angela Davis (1981) highlights, racism enables and reinforces sexual coercion. It sustains sexism by oppressing women of color while also indirectly victimizing white women. Colonial powers used sexual violence as a tool of dominance, from Black slavery (Hartman, 1997) to the brutal violence and exploitation of Vietnamese women during the American War on Vietnam. Rape was made “socially acceptable” and institutionalized in the U.S. military command, where soldiers were ordered to “search Vietnamese women with their penises.” This mass political terrorism sought to undermine the critical role women played in the Vietnamese liberation movement. Additionally, the reproductive poisoning caused by Agent Orange still affects these women today, isolating them from society with no reparations (Bingle, 2023; Davis, 1981).

It stems from the historical racialized policing of sexuality in colonial regimes, institutionalized sexual regulation as a mechanism of social control (Stoler, 2002).

Michel Foucault (1978) explains that shifting sexuality from the public to the private sphere reinforced colonial control, particularly over women. Through increasingly restrictive legislation, those in power were not only able to regulate sexuality but also define the “right” expressions of it; any deviation from these definitions was deemed immoral.

The construction of European identity relied on rigid sexual norms: monogamy, heterosexuality, and the exclusion of interracial relationships (McClintock, 1995). These norms dictated who was considered “acceptable” and who was seen as immoral.

In French Indochina, Métis (mixed-race) individuals disrupted racial and moral boundaries, threatening colonial hierarchies (Hodges, 2017). In response, the French administration institutionalized sexual norms, arguing that Métis children had to be educated by white men to prevent “moral corruption.” Indochinese women, meanwhile, were cast as “immoral prostitutes,” reinforcing European control over both race and sexuality (Stoler, 1995).

Sexuality was weaponized to reinforce racial hierarchies, constructing “whiteness” as both a racial and moral category. Not only did sexuality act as a power structure to justify white settlement in the face of Indigenous “sexual vice,” but it also defined a “European” as someone who understood sexuality as morally restrained within a heterosexual marital unit (McClintock, 1995).

Western colonial narratives positioned the West as masculine and rational, while the East was feminized and mysterious (Said, 1978). The marking of sexuality as an ethnic identity extended from capitalism, Adam Smith’s economic theories categorized races as more or less “civilized” based on European standards of manners and sexuality (Mehta, 1999). French colonial discourses sexualized Indochina, initially conceptualizing it as a male utopia. This doctrine sought to domesticate Indochina, partially through the tactic of moral arbitration of women.

European standards of sexuality were legitimized through scientific narratives, such as Carl Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae (1758). Initially designed to classify plants by reproductive parts, this system was later applied to humans, reinforcing racial hierarchies and European superiority (Schiebinger, 1993).

Linnaeus’ classification of humans into hierarchical racial categories set in motion a “project to be realized in the world in the most concrete possible terms”—if you can order people, you can exert power over them (Schiebinger, 1993; Stoler, 2002).

These colonial structures continue to shape gender, race, and power today. From Israel showing systematically use of colonial structure to enable the use of sexual, reproductive and other gender-based violence against Palestinians and carried out “genocidal acts” against Palestinians in Gaza by destroying women’s healthcare and reproductive health facilities and blocking access to reproductive healthcare

Or discourse around the climate crisis , economic growth, and population control disguises the racist, unequal access to resources that colonialism exploited. A drastic decrease in population in the Global South would make a lesser environmental impact than just a 5% reduction in present consumption levels in the richest countries, countries that have extracted and exploited the majority world (Shiva, 1988). Yet, racialized bodies are only considered when they are accused of overburdening the planet’s resources and whose fertility must, once again, be controlled.

Our bodies were never ours to begin with. But can we reclaim femininity beyond commodification? Can we tell our own stories beyond the colonial gaze?

To decolonize beauty, labor, and identity is to subvert the colonial gaze and reclaim self-determination & repair over our bodies and narratives, both within ourselves and in our relationship with the Earth. No one is liberated until everyone is free! Feminism is a decolonial fight for réparation.

Community.